Vassilis Kroustallis reviews the Hungarian film by Gábor Fabricius on totalitarian regime and resistance, Erasing Frank

Erasing Frank, the debut feature by Gábor Fabricius is best described as a cry in the dark of a totalitarian regime, whose repercussions still seem to echo sensitive ears in our 21st century. Placed on 1983, one year before the Orwellian 1984 (a reference multiply used in the film), it offers a candid portrait of being young and being a suffering hero against all odds; at times it enters into its own dystopian setting which the director has meticulously constructed, and loses its own power.

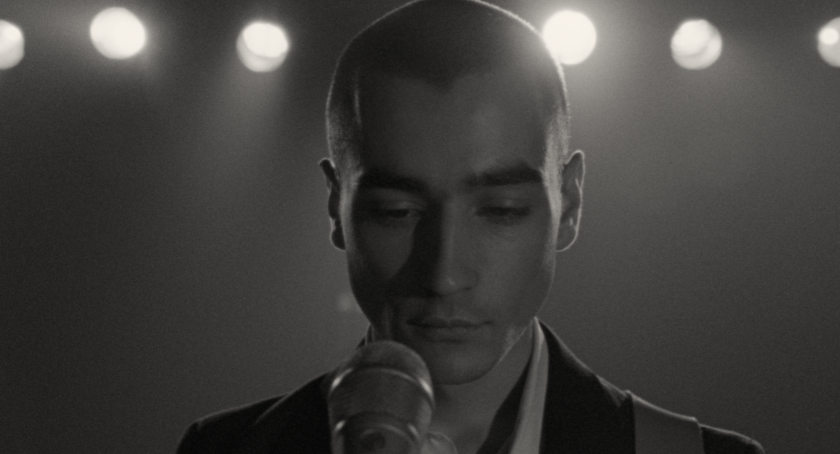

Frank (Benjamin Fuchs) is a singer whose lyrics and concerts -shown before the opening title credits start rolling- a young person who will revert Wittgenstein's dictum of the things one must be silent of into things one must speak of; even in the most liberal-showing Kádár regime that ruled in Hungary during the times of Erasing Frank as well. His girlfriend Anna (Andrea Waskovich) works in a psychiatric hospital and has the means (and the opportunity to forge papers) to secure Frank's detainment there ; in exchange for time in prison.

Frank enters the psychiatric hospital, with the camera following his every step, and enters into a place where grotesque but still overwhelming sad faces reside. After a brief doctor's interview, in which Frank has the chance to meet the silent catatonic Hanna (Kincső Blénesi), the road is open for Frank to experience a situation between reality and the dream.

Erasing Frank, in its black-and-white, 'documentarian' version shown in Venice, will not escalate into Milos Forman's 'Cuckoo's Nest 'direct confrontational route, and is keen to shy away from explicitly depicting torture tactics practiced to political dissidents in the psychiatric hospital. Its cinematic field mostly assumes the element of delusional disguise; a regime self-proclaimed as 'the most progressive regime of the world'. A veteran official Dr. Eros (a commanding presence by Hungarian film professional István Lénárt, in his last role) is able to 'understand' the revolutionary youth, and he can also offer to sacrifice himself -as long as the regime remains intact.

This is a film that its various scenes unfold from the point of view of the always bewildering Frank. His characterization in the film spares us most details about his own craft, and his resisting attitude sometimes becomes a theme too thin to keep the various strands of the plot together. The film's insistence on navigating both the world of the hospital and the outside world, the state radio and resistant groups makes it less of a chronicle of psychiatric treatment, and more of a kaleidoscope of 1980s Hungary. Tall, rigid official buildings alternate with the vast hospital spaces, whereas streets and narrow hallways are the place where human interaction can flourish.

Erasing Frank's treatment of its material sometimes look too sprawling and overwhelming to support one person's battle against a carefully disguised oppressive regime; it has its moments of audience being lost in repetitive scenes. Fuchs' performance is assured, and the film always informs you of its main target and purpose.

Erasing Frank premiered at the 2021 Venice Film Festival (36th Venice International Film Critics Week).